@《1933年淘金女郎》相关热播

@最近更新剧情片

@《1933年淘金女郎》相关影评

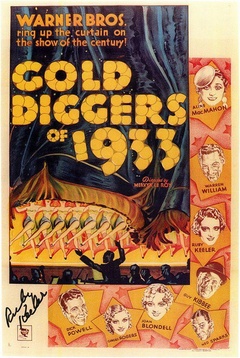

(大学时期的paper,以下内容全部原创,转载请联系本人)经济大萧条是我很迷恋的一个历史时期。它不仅是film noir在美国得以出现、昌盛的条件,还有其余很多类别都在这个背景下繁荣。比如辉煌一时的backstage musicals。虽然我不是特别喜欢歌舞片,但backstage musicals和大萧条真是写research paper时一个立刻想到的话题。以下是这个10月的劳动成果:)Between 1929 and 1932, although not driven to bankruptcy, the major studios of Hollywood were severely affected by the Great Depression. In three years, movie attendance had dropped from 110 million admissions per week to 50 million (Furia and Patterson 66). However, the 1930s saw the flourishing of a specific film genre, the backstage musical. Beginning with The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont 1929) which was both an Oscar and box office winner, the backstage musical reached its peak with a succession of Warner Brothers’ productions in 1933: 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon 1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy 1933) and Footlight Parade (Mervyn LeRoy 1933), all choreographed by Busby Berkeley. This paper investigates the reasons behind Warner Brothers’ success from two perspectives. In terms of their content and form, these musicals especially appealed to the entertainment-hungry and low-spirited audience in the Depression era. In terms of the production and promotion, the studio system and Warner Brothers’ alignment with the Roosevelt administration were favorable to these musicals’ success. Backstage musicals provided the American public with abundant spectacles in tough times, and they also left an aesthetic heritage in the cinematic history.Backstage musicals present the backstage stories of putting on a show. In contrast to integrated musicals, their musical numbers are often separated from the narrative,appeared as rehearsals. As the off-stage stories progress toward a happy ending, the musical numbers also turn to a successful stage performance at the end, put up by the collective effort of the crew. A closer examination below of the content and the form of Warner Brothers’ backstage musicals shows how Warner Brothers supplied the Depression-era audience with what they hoped to see on screen. They did so by providing the audience a mixture of escapism and realism.On one hand, Warner Brothers’ backstage musicals as a form of entertainment served the function of entertaining the audience, and in the context of the Great Depression, they tried to fulfil the public need for escapism. In his essay “Entertainment and Utopia”, Richard Dyer identifies two important features of entertainment: “escape” and “wish-fulfilment”. He states that entertainment provides the means by which alternatives and hopes can be imagined (20). It is reasonable to assume that the Depression-era audience especially sought from films elements of romance, comedy and a happy ending, to give them a moment’s escape from the gloomy reality. Furthermore, these backstage musicals gave an affirmation to the traditional American beliefs: “that hard work would pay off, that individuals were in charge of their own destiny, and that simple good neighborliness would see America through the crisis” (Canning 51). The crews are often caught in an economic predicament, and the whole film depicts their efforts to put on a successful show to overcome the obstacles. After watching the film, the audience felt emotionally uplifted as they came out of the theatre.On the other hand, Warner Brothers did not merely make backstage musicals escapism entertainment, but they also made certain social commentaries through the setting and the plot. Compared to many films at the same time which “completely avoided the reality of what was happening in the rest of the country” (Kobal 90), Warner Brothers’ backstage musicals were highly socially conscious. In fact, the setting of these films was the Great Depression itself, in which producers, writers and showgirls faced poverty and unemployment, arousing much resonance with the audience. Many of the musical numbers directly used the Great Depression as their motif. For example, the opening of Gold Diggers of 1933 is an ironic spectacle “We’re in the Money”. The rehearsal is then interrupted by creditors who come to seize the costumes and close down the show because of the producer’s outstanding debts. The ending of Gold Diggers of 1933, “Remember My Forgotten Man”, provides an even stronger social critique of the aftermath of World War I. The musical number shows soldiers marching off to the war and also depicts the unemployment, poverty and broken families in the aftermath. The number is inspired by the Bonus March event in 1932, when 15,000 unemployed veterans paraded in Washington D.C. to demand for money and job (Rubin 73).In addition, a key figure in the success of these backstage musicals was Busby Berkeley, the choreographer for Warner Brothers’ musical numbers. His distinctive kaleidoscopic spectacles completely won over the Depression-era audience. When Footlight Parade was premiered, Daily Boston Globe acclaimed that “no more lavish, impressive and spectacular musical talkie has ever been made” (Hallett 11). Los Angeles Times said that “the audience at the premiere at Warner Brothers Hollywood Theatre was under a spell” (Schallert A9). Busby Berkeley fully took advantage of the mobile camera to show the performances from multiple angles. The camera could pan and tilt; it could zoom to a close-up of the dancer; it could shoot overhead to present geometric patterns formed by dancers; and it could even track through a line of dancers’ legs. The audience gained a completely new experience which they could not enjoy even if they were sitting in the best seats watching a live musical. As Gene Kelly described it, Busby Berkeley numbers were not dance numbers, but cinematic numbers (Pike 11).Turning to the production side of these backstage musicals, the studio system, which had already been in place by the time, allowed for the thriving of this specific genre. The studio produced films in the same way well-run factories manufactured products. Films were manufactured on a regular basis through the production chain. The studios took advantage of specialized labor to maximize efficiency and profits. Musicals especially suited this mode of production, as studios gathered various talents (directors, choreographers, songwriters, screenwriters, etc.) to form a repertoire. They worked in their specialized departments and collaborated to develop a complete musical. Because of the formulaic production and the consistency of labor, musicals from a studio usually carried their own trademarks. Steven Cohan stresses the importance of “standardization” in the introduction of his book Hollywood Musicals, The Film Reader: “Individual artists could aim high but as far as studios were concerned the musical remained an industrial product, its value assured through its standardization, and numbers served this aim” (11). He points out when promoting a musical, the trailer mostly focused on the musical numbers. By showing a musical star and lavish spectacles, the studio sent the message that the upcoming musical contained the same elements as its previous hits yet surpassed them (11). Therefore standardizing and trademarking its musicals helped Warner Brothers build a stable audience.One thing special about Warner Brothers was that unlike other majors, the company was a family-run business, which contributed to its exploitation of the studio system to extreme during the Great Depression. The Depression intensified production control and made Warner Brothers “virtually a self-contained world with each department doing its individual part for the collective goods” (Hoover 145). In 1932, Warner Brothers had an average production cost of $200,000 per feature, which was the second lowest of the major. MGM, for example, had an average of $450,000 ((Hoover 146). The statistics provided evidence that Warner Brothers indeed organized its production economically and efficiently.Just as musicals played an important role in the film’s transition to sound, the development of sound technology was surly an essential condition for turning out these musical spectacles. Warner Brothers was a pioneer in the industry’s conversion to sound, and it had maintained its emphasis on technology as a crucial factor of making good movies. In the early 1930s, Warner Brothers and most of the other studios changed from making sound-on-disc films to sound-on-film films. Sound-on-film technology made more flexible filming available, and also opened up many possibilities for recording, and postproduction editing of these musicalsAt last, Warner Brothers in the Depression era was identified as a firm supporter of the Roosevelt administration and the New Deal, and it did exploit this relationship when promoting films. There is much evidence suggesting Warner Brothers’ alignment with the Roosevelt administration. Some lies in these backstage musicals themselves. Warner Brothers made films about working-class people, and upheld the idea that collectivist spirit pulled people through crises, which resonated with the New Deal’s ideology of collectivism. Warner Brothers’ backstage musicals also made direct references to the Roosevelt administration. An example would be the ending number of Footlight Parade, where a marching chorus revealed a huge portrait of Roosevelt. Apart from their work, Warner Brothers’ engagement in public political events also demonstrated them as advocate of the Roosevelt administration. For example, during the election period, they held a large rally in Hollywood bowl, where celebrities in the film industry attended and people participated in a parade to support Roosevelt’s candidacy (Robbins 122).Warner Brothers’ advocacy of the Roosevelt administration was reflected in their promotions. As A.S. Robbins puts it, Warner Brothers were “eager to capitalize on Roosevelt’s popularity and associate his charisma with Warner Bros. films” (Robbins 123). The advertising of 42nd Street provides an example of how Warner Brothers “capitalize on Roosevelt’s popularity”. In one poster, Warner Brothers put “Warner Brothers welcome Franklin D. Roosevelt and John Nance Garner” on the top, followed by the portraits of the president and the vice president. They also put “celebrating inaugural week” and “New Deal entertainment” together in a circle in this poster to send the message that the upcoming Warner Brothers’ musical was just as promising as the new administration. Another example is the appearance of the Blue Eagle in Footlight Parade, which was a symbol of National Recovery Administration. At that time, it was a common phenomenon that companies in other industries displayed the Blue Eagle on their products and consumers were encouraged to buy from these companies. Warner Brothers were in a sense also marking their products with the Blue Eagle in the same way these companies did.In conclusion, Warner Brothers’ backstage musicals are a distinct product of the Great Depression. They were able to attract a huge number of audience because they offered them a mixture of escapism and realism. Warner Brothers took full advantage of the technology development, and they exploited the studio system to manufacture these musicals with their own trademarks efficiently. When it came to promotion, Warner Brothers utilized their alignment with the Roosevelt administration to gain them favor of the audience. Because of these factors, Warner Brothers’ backstage musicals were a flourishing phenomenon in the early 1930s, and they also contribute significantly to the musical genre and the film media as a whole. 2014.11Works CitedCanning, Gregory A. The Moral Importance of Entertainment: Hollywood, Censorship, and Depression America, 1933 to 1941. Dissertation, Saint Mary's University. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI, 1999. (Publication No. MQ47673.)Dyer, Richard. “Entertainment and Utopia.” Hollywood Musicals, The Film Reader. Ed. Steven Cohan. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.Furia, Philip, and Laurie Patterson. The Songs of Hollywood. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. Print.Hallett, Mat. “New Films Reviewed: Metropolitan Theatre ‘Footlight Parade’.” Daily Boston Globe 21 Oct. 1933: 11. Print.Hoover, John Gene. The Warner Brothers Film Musical, 1927-1980. Dissertation, University of Southern California. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI, 1985. (Publication No. DP22262.)Kobal, John. Gotta Sing Gotta Dance: A History of Movie Musicals. New York: Exeter Books, 1983. Print.Pike, Bob and Dave Martin. The Genius of Busby Berkeley. Los Angeles: CFS Books, 1973. Print.Robbins, Allison Susanne. Let’s Face the Music and Dance: Hollywood Musicals and the Mediatization of Broadway, 1933-1939. Dissertation, University ofVirginia. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI, 2010. (Publication No. 3442304.)Rubin, Martin. “The Crowd, the Collective and the Chorus: Busby Berkeley and the New Deal.” Movies and Mass Culture. Ed. John Belton. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996. Print.Schallert, Edwin. “’Footlight Parade’ Spectacular Picture”. Los Angeles Times 10 Nov. 1933: A9. Print.Filmography42nd Street. Dir. Lloyd Bacon. Warner Bros, 1933. Film.Footlight Parade. Dir. Mervyn LeRoy. Warner Bros, 1933. Film.Gold Diggers of 1933. Dir. Mervyn LeRoy. Warner Bros, 1933. Film.